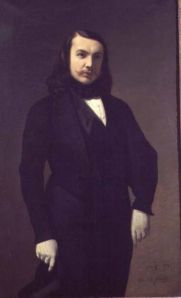

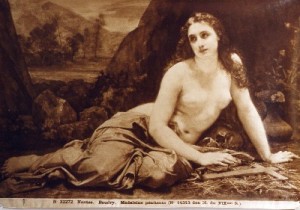

Theophile Gautier – Mademoiselle de Maupin

I cannot begin to convey how much I love this book. I personally think it’s the finest thing Gautier ever wrote. It is a fictionalised account of the life of Madeleine de Maupin, an historical figure infamous for her habit of cross-dressing, her duelling abilities and her theatrical talent. She is even said to have abducted a nun she fell in love with from a convent, but sadly there is very little evidence to support this.

The novel was published in 1835, and caused quite a stir. Reading it, it’s somewhat incredible that it got published at all, considering its themes of cross-dressing, homosexuality, and frank discussions of sexual relations. Not to mention Gautier’s defence of the ‘art for art’s sake’ philosophy, and his argument that the artistic world is purely decorative and inherently amoral – sentiments that would be echoed years later by a certain Mr Wilde you may or may not have heard of.

The story begins with the sorrows of a young aesthete, the Chevalier d’Albert, who is dissatisfied with the inadequacies of nature compared to art, and longs to find a mistress who will live up to his aesthetic ideal. He finally settles on a beautiful young widow, Rosette, whom he sees more as a cipher for his fantasies than a lover in her own right. It would be easy to find d’Albert and his often blatant misogyny appalling (at one point he suggests that a woman may as well jump off the roof after the age of thirty, because her looks are fading), but somehow Gautier manages to deflect this, partly through making d’Albert somewhat ridiculous. How can you take him seriously when he states that he wants to kill men who seem to be a better-looking version of himself, because they have committed an act of ‘plagiarism’? Obviously, Gautier took his ideas of art and aesthetics very seriously, but I cannot help but feel that he had a slightly tongue-in-cheek attitude when representing his young hero. Everything is thrown into turmoil when d’Albert finally sees his vision of perfection in another human being while holidaying at his mistress’s house. However, the object of his affections is (shock! horror!) a man. Or so he thinks…

The narrative is then continued by the eponymous heroine, Madeleine de Maupin, who is dissatisfied with the limited role in life that she can play as a woman, and curious to know what men are really like when they think there are no females around to impress. She masquerades as a young nobleman, Theodore, and quickly becomes disillusioned with the male sex, before finding herself in the awkward position of having both Rosette and d’Albert fall in love with her. Not that she finds it awkward for too long, and is soon doing all she can to make the most of her unusual situation.

The novel was revolutionary in so many ways, not just because of its controversial subject matter but also because it acknowledged that women have desires and aspirations of their own, and also admire the subtleties of artistic perfection. It makes gender performance obvious, and is equally merciless to both sexes. Incidentally, the aspect of gender performance in Mademoiselle de Maupin is a subject I am especially intrigued by, and I’ve written a longer essay on the subject which is here, if you’re interested.

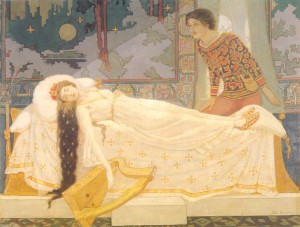

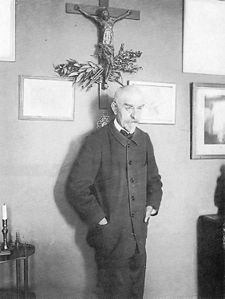

John Duncan

Decadent Handbook is one month old now. Huzzah! A brace of prostitutes and absinthe all round! To celebrate, I thought I’d do another art post.

John Duncan (1866-1945) was a Scottish painter whose subject matter was closely associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement, but is generally referred to as a Symbolist. He experimented a lot with different techniques and styles, and his work has a mystical, otherworldly quality. He claimed to hear ‘fairy music’ when he painted, and he married a girl who claimed to have found the Holy Grail in a well at Glastonbury. The marriage didn’t last. I can’t imagine why. The images have come out quite small, but you should be able to click to enlarge.

I think this is probably my favourite. I love the bright, jewel-like colours, not to mention the fact that there is a floating woman with her head on fire in the foreground. Despite the fact that this is an allegory of love, Duncan still manages to make it strangely creepy.

Duncan took a lot of inspiration from Celtic myth and legend. There’s something about his paintings that remind me of Botticelli.

Duncan often used blocks of pastel colours, giving his paintings a dream-like quality.

This painting of the Irish saint being held aloft by a couple of angels is reminiscent of medieval art in its two-dimensionality, and the stained-glass like quality of the angels’ robes.

The Great Courtesans

I’ve recently finished reading a fascinating book, Joanna Richardson’s The Courtesans, a history of the twelve greatest women of pleasure in the Demi-Monde. These women were a far cry away from the typical modern perception of prostitutes as victims. They used their sexual allure and their sharp wits to accumulate a vast amount of power and wealth, far greater than many of their ‘respectable’ contemporaries. Reading about these remarkable women, I could see clear parallels with the ‘femme fatale’ that the Decadents were so fond of. I enjoyed the book very much, and thought I’d make a quick note of the grande horizontales whom Richardson covers.

1. Blanche d’Antigny (1840-74)

Blanche (born Marie-Ernestine Antigny), is widely believed to have been the inspiration for Emile Zola’s infamous courtesan, Nana. She certainly met Nana’s physical description, burnt through money at the same rate, and died a similar death to the heroine at the young age of 33. A part-time actress, she could list a Russian prince, Maharajahs and French bankers amongst her conquests. She kept a magnificent set of rooms in Paris, draped with turquoise satin and populated by liveried footmen, where she threw extravagant parties for her friends. She is infamous for appearing in public draped in diamonds.

2. La Barucci (1837[?]-70/1)

La Barucci (Giulia Beneni) won favour through her Italian looks, her indefatigable determination to win the lover of her choice, and her charming, child-like spontaneity. She would proudly show off her jewellery cabinet to her visitor, the contents of which were said to be worth millions, and she kept her visiting cards in a china bowl by her fireplace – cards which bore the names of nearly every name in high society at the time. When meeting the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII), she was told to behave with decorum. Upon being introduced, she promptly let her dress fall to the ground, without a word of warning. When she was reprimanded, she exclaimed, “What, did you not tell me to behave properly to His Royal Highness? I showed him the best I have, and it was free!”

3. Cora Pearl (1835-86)

Cora Pearl (Eliza Emma Crouch), an English emigrant, was infamous for being the most unfeeling of the great courtesans, only loving men for what they could give her. However, given that her initiation into sexual activity was in the form of a rape, one cannot help but sympathise with her desire to exact revenge on mankind, ruining them with her charms, then leaving them when she had got all she could. She quickly progressed through the European aristocracy, and had an affair with Prince Napoleon that lasted for many years. She used her vast accumulation of wealth to purchase luxurious apartments in the rue de Chaillot, fitted with a bath of rose marble, her initials inlaid in the bottom with gold. She was a keen sportswoman, and was said to bestow far more affection on her horses than her dejected lovers. She once appeared on the Paris stage wearing boots with buttons made from huge diamonds, the soles also incrusted with the precious stones. The Prince once sent her a van-load of rare orchids, and she threw a party where she danced the hornpipe, dressed as a sailor, over the valuable flowers. One lover sent her a box of marrons glaces, each one wrapped in a thousand franc note. Unfortunately for Cora, the life of luxury did not last. The fall of the Second Empire brought an end to her power, and she died in poverty.

4. Esther Guimond (d. 1876)

Esther Guimond was one of the courtesans who had the most influence on the Press and politics of her time. Once she had established herself with a selection of wealthy lovers, her apartments regularly entertained distinguished writers and politicians, who were won over by her sharp wit and amusing anecdotes. She managed to retain her influence even as age set in, and entertained influential men at her dinner parties well into her old age.

5. La Paiva (1819-84)

La Paiva clawed her way up from the Moscow ghetto to unbelievable wealth, first as a Marquise and then a Countess. She is also the most unpleasant of the courtesans discussed by Richardson, carelessly leaving a trail of men behind her as she used up their resources, and showing no regret at the death of her child. She had an almost supernatural belief in the power of the human will to achieve certain ends, and it certainly seems to have worked for her. Her luxurious hotel on the Champs Elysees stands to this day as a testament of her obscene wealth. The staircase was made from real alabaster, and the salon had a magnificent ceiling, designed by Baudry, depicting day chasing away the night. She could only consider the value of something in the terms of how much it cost. She was also known to be cruel – she shot a horse which threw her, and was a hard mistress to her many servants, unforgiving of the slightest error. La Paiva ended her days at the castle of her last husband, Henckel von Donnersmarck, who was unfailingly devoted to her. There was a legend that Donnersmarck’s second wife, well-born and youthful, unlocked a room in the castle that her husband kept carefully closed up, finding the body of La Paiva, preserved in alcohol. An attractive legend, albeit one that seems to have wandered straight out of the pages of a Perrault fairytale.

6. Mademoiselle Maximum (1842-94)

Mademoiselle Maximum (Leonide Leblanc) earned her nickname through her great hunger for luxury and excess. Naturally capricious, she abandoned her burgeoning career as an actress in order to go travelling, before returning to Paris and the stage. Her personal charms seem to have earned her forgiveness for her flightiness. She courted publicity, and also seems to have been a compulsive liar. She had many generous lovers, but was unable to hold onto any of them for long. She was similarly careless with her material wealth – as much as she loved her luxuries, she often speculated unwisely, and was eventually forced to live more modestly. In spite of this, she continued to be admired until her death.

7. Marguerite Bellanger (1840-86)

Marguerite was often criticised for her rustic, tomboyish manners, but it was this unaffected quality in her that attracted the attentions of Napoleon III, who became so infatuated with the courtesan that the Empress eventually had to intervene in order to avoid a public scandal.

8. Caroline Letessier (dates unknown)

Caroline was a woman who disappeared back into the obscurity from whence she came, after spending a few glittering years as one of the stars of la garde. She appeared at parties in elaborate gowns, strewn with jewels, and once danced so much that her dress was nearly torn to shreds. She claimed to ‘deal in Grand Dukes’, and defiantly appeared in public alongside ‘respectable’ women, not afraid to reply insolently to anyone who dared to disparage her.

9. Alice Ozy (1820-93)

Alice Ozy (Julie-Justine Pilloy) was renowned for her charm, wit and financial intelligence. She started – as did many courtesans – in the theatre, where she stole the heart of the young Duc d’Aumale. It was an affair that was to establish her, although she did not return his loyalty, and moved on to a series of conquests, including Theophile Gautier, who seems to have been positively tormented by her. Her financial acumen meant that she could retire in wealth, but her old age seems to have been haunted by loneliness, and a regret for the days that had gone.

10. Marie Duplessis (1824-47)

Marie Duplessis would win immortality as the inspiration for Dumas’ La Dame aux Camelias. She was always fragile, and seemed to have known that she would not live long judging by how fiercely she lived in the small time allotted to her. She was passionate about the theatre, and hated to miss a performance of any new play. Her charm and sense of decorum meant that she was accepted into respectable society – a rare thing for a courtesan. She won the heart of Franz Liszt, who gave her piano lessons, and would remember her wistfully years later. When she died at the age of just twenty-three, her belongings were sold to fashionable ladies, clamouring for a souvenir of this charming courtesan.

11. Apollonie Sabatier (1822-89)

Madame Sabatier, often referred to as ‘La Presidente’ was the hostess of the most culturally rich salon in Paris, and is famously the inspiration for Charles Baudelaire’s ‘white Venus’ poems. A great patron of the arts, Apollonie seems to have been the most endearing and respected of the courtesans – evidence of her tender-heartedness can be found in her personal letters to Baudelaire. She won the admiration of Flaubert, Gautier and Jean-Baptiste Clesinger amongst many others.

12. Mogador (1824-1909)

Mogador (La Comtesse de Chabrillan) is a tragic figure amongst her more frivolous contemporaries, due to her desire to be a respectable woman. Winning fame for her ability to dance magnificently, she had entered prostitution through a belief that there was nothing else for her, and she would always regret it. She eventually married a respectable nobleman whom she loved very much, but his family refused to accept her. The couple were forced to leave for Australia in order to keep afloat financially, where Mogador initiated a successful career as a writer. However, she soon had to return to Paris for the sake of her health, and after just a few years together her husband died. She committed her life to giving lectures and to charitable causes, but she never gained the respectability she so dearly desired. She is something of a pathetic figure compared to her more ruthless, morally lax, contemporaries, suffering acutely because she hadn’t the heart (or lack thereof) to be a true courtesan.

Didn’t realise this would be quite such a long post – sorry about that!

The poetry of Ernest Dowson

Poor Ernest Dowson. Of all the Decadents, I think he is the one I feel for the most. Okay, so his death from consumption at the tender age of 32 was mostly brought on by his inability to stay away from the absinthe. And yes, falling in love with an eleven-year-old girl is more than a little controversial by today’s standards, but it’s not as if his relationship with her was ever physical. He had his prostitutes for that. Born in London, Dowson’s father was in the dry-docking business, but young Ernest was more interested in poetry than trade. He led an active and varied social life, and was a member of the Rymers’ Club, frequently contributing to the popular magazines of the day. But his lifestyle could not be supported on the income this offered. After the suicides of both his parents – who were also consumptives – Dowson went into a decline. The writer Robert Sherard (biographer of Oscar Wilde) found Dowson destitute and sick in a London bar, and took him back to his cottage. Within a few weeks Ernest had died.

Sadly, Dowson isn’t that widely known these days, despite his poem Vitae Summa Brevis giving us the phrase ‘days of wine and roses’. This is great shame, because he really did write some of the most evocative, sensuous verse of the period, and doubtlessly would have given us much more if it hadn’t been for the his determination to self-destruct. His most famous poem is probably Non Sum Qualis eram Bonae Sub Regno Cynarae, supposedly inspired by his unrequited and chaste love for the child waitress, Adelaide Foltinowicz. My favourite, however, is a poem called Absinthia Taetra, a poignant ode to Dowson’s choice poison.

Absinthia Taetra

Green changed to white, emerald to an opal: nothing was changed

The man let the water trickle gently into his glass, and as the green clouded, a mist fell from his mind.

Then he drank opaline.

Memories and terrors beset him. The past tore after him like a panther and through the blackness of the present he saw the luminous tiger eyes of the things to be

But he drank opaline.

And that obscure night of the soul, and the valley of humiliation, through which he stumbled were forgotten. He saw blue vistas of undiscovered countries, high prospects and a quiet, caressing sea. The past shed its perfume over him, to-day held his hand as it were a little child, and to-morrow shone like a white star: nothing was changed.

He drank opaline.

The man had known the obscure night of the soul, and lay even now in the valley of humiliation; and the tiger menace of things to be was red in the skies. But for a little while he had forgotten.

Green changed to white, emerald to an opal: nothing was changed.

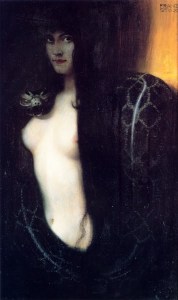

Franz von Stuck

The paintings of the Bavarian artist, Franz von Stuck (1863-1928), are full of strange, mythological creatures, femme fatales, and allegorical figures.

It is difficult to tell whether the Sphinx is kissing or devouring her male victim. His vulnerability and surrender, and her sexual aggression, are a marked reversal of traditional gender roles at the time, yet also display a fear of female sexuality.

A similar theme appears in Stuck’s allegory of Sensuality. Like the Sphinx, the female nude has her face obscured by shadow, and the eye is drawn to her breasts. The vast serpent twined around her body is reminiscent of Eve and the fall from Eden. It is at once compelling and disturbing.

This is one of my favourites. I really like how the lovers blend seamlessly into the darkening landscape.

The women’s dresses seem to be an extension of their bodies. They look almost like flames or flowing water.

This figure of Sin is very similar to Sensuality, right down to the vast serpent. Clearly, sin and sensuality are indicated to be one and the same.

A triumphant Salome dances, as John the Baptist’s head is exhibited in the background.

I’m not entirely sure how I feel about a lot of Franz von Stuck’s art. I’m drawn to it from an aesthetic point of view, and I like all the dark imagery, but I feel like it often represents ‘woman’ and ‘corruption’ as synonymous. I do realise that there was a lot of inherent sexism in the art and literature of the time, but I’m not sure that I like being beaten over the head with it quite so much. But then, perhaps I’m reading too much into it. I’d appreciate any thoughts on the subject.

A Rebours

“Nature… has had her day” – Des Esseintes

I can’t believe I haven’t discussed this book already. I think I’ve been so focussed on introducing aspects of the movement that are less well-known that I have slightly neglected the classics. And Joris-Karl Huysmans’ A Rebours (usually translated into English as Against Nature or Against the Grain) is quite possibly the classic Decadent text. Huysmans (1848-1907) wrote A Rebours in 1884, fully expecting it to be a complete flop. Instead, it became notorious. Many critics were appalled by its apparent lack of morality, while young Dandies and Aesthetes were attracted to it for its idolisation of art and sensation. It quickly became known as a guidebook to Decadence. As if further recommendation were needed, it is widely believed to be the unnamed “poisonous French book” read by Dorian Gray, which contributes to his corruption.

Having said that, A Rebours is not a book I would recommend to a complete beginner in Decadent literature. Those unfamiliar with the style and ideology may find it difficult to relate to, not least because there is no real plot to speak of. Hardly anything actually happens. The basic premise is that Des Esseintes, the novel’s anti-hero, has become so disillusioned with modern society and the pettiness of those around him that he decides to hole himself up in a rural French mansion, cut off from everyone, and dedicate himself to the pursuit of sensation. Finally, his fragile health breaks completely, and he is compelled to return to Paris. I love this book. As far as I’m concerned, plot and action don’t matter so much as long as a book is beautifully written and gives me something to think about. And A Rebours certainly does that.

Some of the most memorable parts:

* Des Essseintes has a very eccentric take on interior design. He decorates one room of his mansion like the cabin of a ship, and spends days agonising over which colour will be aesthetically pleasing in both daylight and candlelight (he eventually chooses burnt orange).

* He rhapsodizes over the art of Gustave Moreau, and collects etchings depicting torture and death.

* A whole chapter is devoted to Des Esseintes’ library. He expresses contempt for the popular fiction of the day, but greatly admires Baudelaire and Verlaine. He also expresses devotion to the more controversial of the Latin authors such as Petronius.

*Des Esseintes develops a love for perfumes, and the scents evoke memories of his former lovers, including an androgynous female acrobat, and an adolescent boy.

* He decides to collect exotic flowers, which resemble diseased organs, alien entities, and strange sculpture. He can only love things of nature when they look artificial.

* In one of the more amusing passages, Des Esseintes, after reading the novels of Dickens, decides to take a trip to England. On the way to catch his boat,he stops off at a British cafe in Paris, and eats a vast meal surrounded bt Englishmen. After this, he decides that he might as well return home, because he has had a better English experience than he would if he went to the actual country.

* He decides to decorate the shell of a tortoise he has purchased with gem-stones in order to increase its artificiality. The unfortunate creature promptly dies.

There is something touchingly vulnerable about Des Esseintes that makes you want to continue reading in spite of how appalling his behaviour often is. His complete devotion to his Decadent lifestyle, in spite of his detrimental impact on his health, and despite the fact that it never really gives him the satisfaction he craves, is almost admirable. He is simply trying to find the right way to live. And isn’t that what we’re all doing?

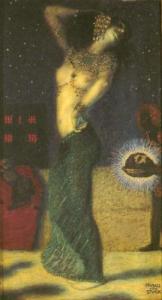

Carlos Schwabe

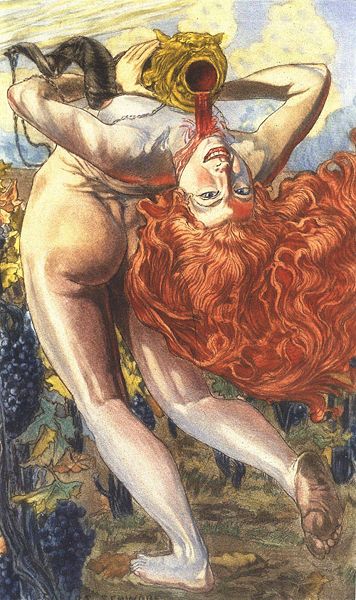

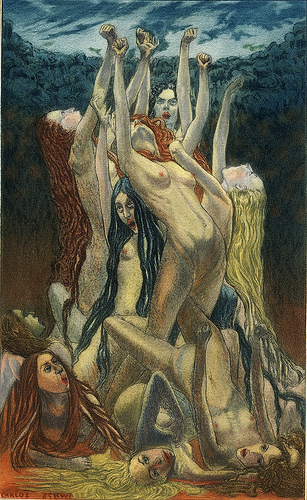

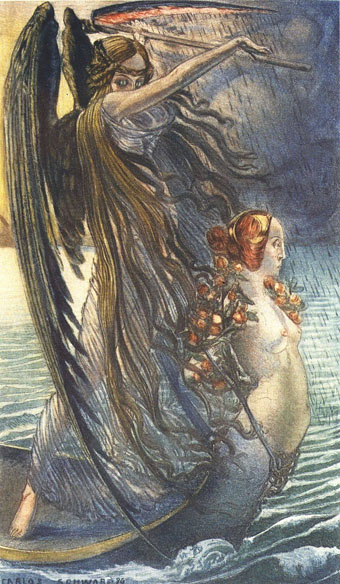

Carlos Schwabe (1877 – 1926) is one of the more disturbing Symbolist artists. He seems to have had an obsession with death (possibly associated with the demise of a close friend when he was 17), and his paintings often contain allegories of suffering. He also displayed an interest in Decadent literature, and the following are all illustrations painted by Schwabe for Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal.

Benediction

The Love of Wine

Revolt

The Death of Lovers

Spleen and the Ideal

The Poet and the Muse of the Ideal

I find his work disturbing and compelling at the same time. Which, of course, is the mark of a true piece of Decadent artistry.

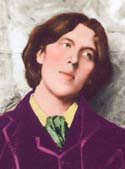

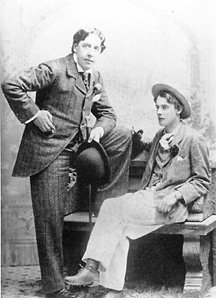

Wilde’s ‘Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young’ – the Decadent Manifesto

What follows is what I think of as the definitive decadent manifesto – Oscar Wilde’s Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young. First published in December 1894, in the first (and only edition of Oxford student magazine, The Chameleon, this collection of epigrams defy conventional morality, elevate art above nature, and hold utility in the utmost contempt. It doesn’t really matter whether Wilde truly believed in these philosophies. The point is that he wrote them.

Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young

The first duty in life is to be as artificial as possible. What the second duty is no one has as yet discovered.

Wickedness is a myth invented by good people to account for the curious attractiveness of others.

If the poor only had profiles there would be no problem in solving the problem of poverty.

Those who see any difference between soul and body have neither.

A really well-made buttonhole is the only link between Art and Nature.

Religions die when they are proved to be true. Science is the record of dead religions.

The well-bred contradict other people. The wise contradict themselves.

Nothing that actually occurs is of the smallest importance.

Dullness is the coming of age of seriousness.

In all unimportant matters, style, not sincerity, is the essential. In all important matters, style, not sincerity, is the essential.

If one tells the truth, one is sure, sooner or later, to be found out.

Pleasure is the only thing one should live for. Nothing ages like happiness.

It is only by not paying one’s bills that one can hope to live in the memory of the commercial classes.

no crime is vulgar, but all vulgarity is crime. vulgarity is the conduct of others.

Only the shallow know themselves.

Time is a waste of money.

One should always be a little improbable.

There is a fatality about all good resolutions. They are invariably made too soon.

The only way to atone for being occasionally a little over-dressed is by being always absolutely over-educated.

To be premature is to be perfect.

Any preoccupation with ideas of what is right and wrong in conduct shows an arrested intellectual development.

Ambition is the last refuge of the failure.

A truth ceases to be true when more than one person believes in it.

In examinations the foolish ask questions that the wise cannot answer.

Greek dress was in its essence inartistic. Nothing should reveal the body but the body.

One should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art.

It is only the superficial qualities that last. Man’s deeper nature is soon found out.

Industry is the root of all ugliness.

The ages live in history through their anachronisms.

It is only the gods who taste of death. Apollo has passed away, by Hyacinth, whom men say he slew, lives on. Nero and Narcissus are always with us.

The old believe everything: the middle-aged suspect everything: the young know everything.

The condition of perfection is idleness: the aim of perfection is youth.

Only the great masters of style ever succeed in being obscure.

There is something tragic about the enormous number of young men there are in England at the present moment who start life with perfect profiles, and end by adopting some useful profession.

To love oneself is the beginning of a life-long romance.

Wilde with sometime lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, Oxford 1893

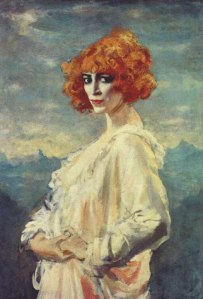

Luisa Casati

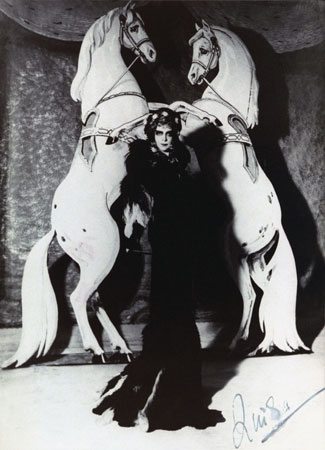

'The Marchesa Luisa Casati With a Greyhound' by Giovanni Baldini

“I want to be a living work of art!” exclaimed Luisa Casati (1881 – 1957), the woman who astounded Europe with her extravagant parties, played muse to many of the artists of the age, and burnt through a vast fortune, before ending her days in poverty in a London attic. She was more than twenty-five million US dollars in debt at the time of her death – surely a woman who knew how to party.

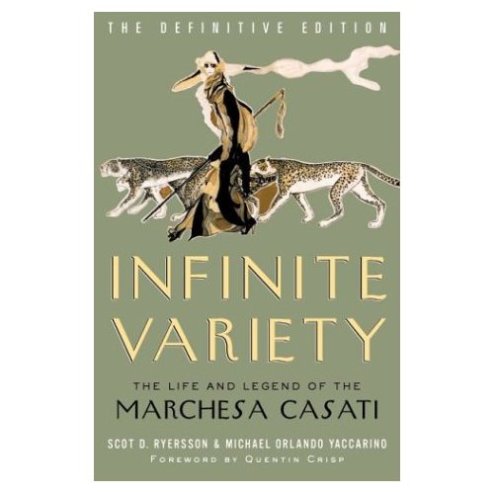

Casati by Augustus John

I love the Marchesa Casati. I recently finished her biography, Infinite Variety, by Scot Ryersson and Michael Yaccarino, which I recommend very highly as a portrait of a remarkable woman, the decline of the golden age in Europe, and a fascinating piece of art history.

The Marchesa was infamous for her night-time strolls, naked under her elaborate furs, leading a couple of pet cheetahs on diamond-studded leashes. She was the lover of Gabriele D’Annunzio, and inspired his work throughout his life. Countless artists were fascinated by her death-like pallor, her vast, kohl-rimmed, green eyes, her vivid red hair. She transformed her numerous homes into elaborate fantasies. She spent thousands on her elaborate costumes, and her even more elaborate parties. Her dinner tables were served by footmen painted in gold leaf. It was said that she had obtained wax images of her past lovers which contained their ashes.

Casati by Alberto Martini

Needless to say, I find her enthralling.There is ridiculously little literature available about Luisa (in addition to the biography mentioned above, an anthology of the art she inspired, Portrait of a Muse, is about to be published). But to learn more about this fascinating woman, you can go to her official website, marchesacasati.com, or read this article on Dandyism.net.

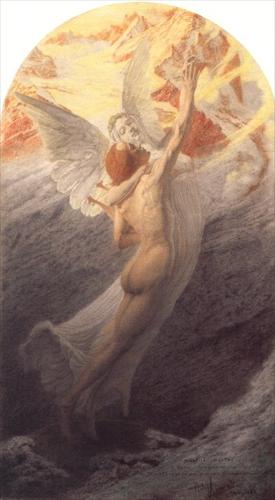

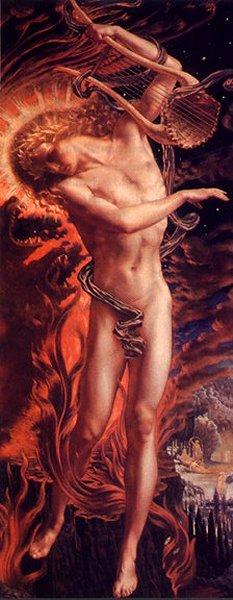

Jean Delville

I try not to have favourites, I really do. Mostly because I’m fickle in my affections and tend to change my mind every few months anyway. Nevertheless, I have no hesitation in stating that Jean Delville (1867-1953) is possibly my favourite Symbolist painter. He had a keen interest in the Occult, and founded the Salon d’Art Idealiste in his native Belgium.I think I love him so much because I’m instinctively drawn to art that’s a little bit disturbing. Also, I like that he’s one of the few Symbolist artists who didn’t shy away from depicting naked men. There’s a complete dearth of manflesh in nineteenth-century art, if you ask me.

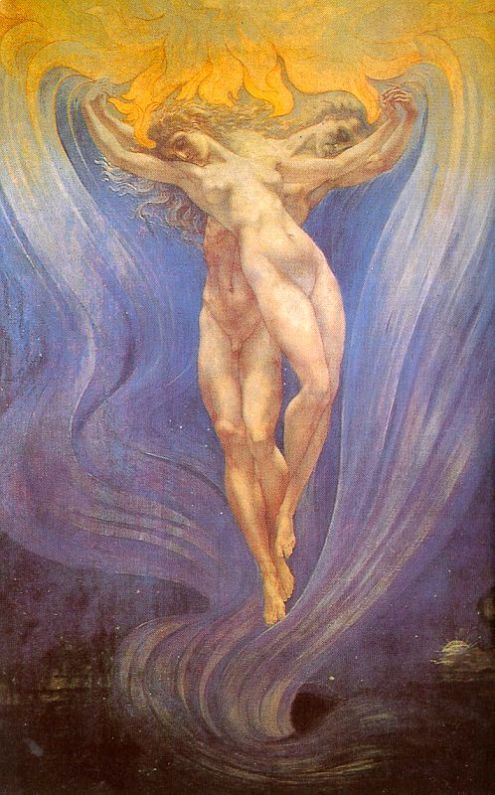

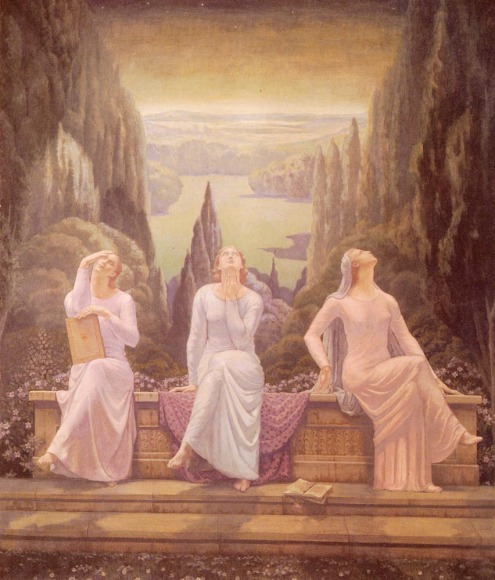

The Love of Souls

The School of Silence

Satan's Treasures

Orpheus

More Delville art will be coming up in the future.